The year 2020 marks 150 years since the birth of Maria Montessori. Although schools employing the “Montessori Method” are well known for their hands-on approach to early childhood development, the story of the person behind the method is less known. Maria Montessori is a pillar of education, and the inspirational story of her life is as relevant today as it was more than a century ago.

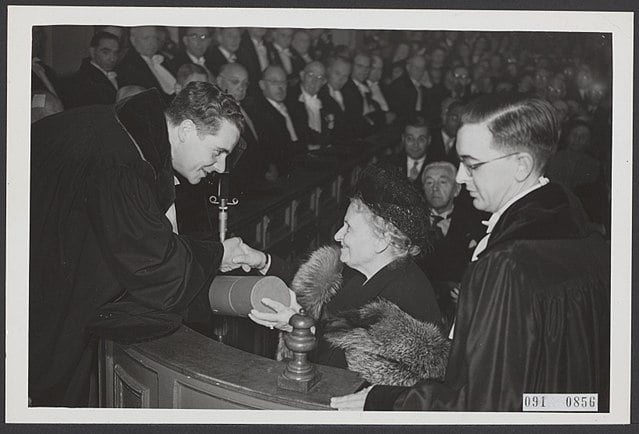

Born August 31, 1870 in Chiaravalle, Italy, Montessori was the first woman ever granted a medical degree by an Italian University. After earning her degree in 1894 from the University of Rome, she pursued post-graduate work in psychiatry. This led her to spend a considerable amount of time trying to help people who were placed in insane asylums.

Some of these patients were children who were so intellectually deficient, they were labeled insane. But when Montessori examined them, she concluded that this was not a medical issue at all. “I, however, differed from my colleagues,” she once wrote, “in that I felt that mental deficiency presented chiefly a pedagogical, rather than mainly a medical, problem.” To her, this was an education issue.

So, despite having recently become the first woman medical doctor in Italy, Montessori put aside her work as a doctor to become director of a state school for intellectually deficient children.

Montessori believed that intelligence and talent were developed, rather than innate qualities that cannot be changed. She exemplified what Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck calls a growth mindset.

Working sometimes thirteen hours per day, Montessori developed new materials and methods to improve the education of children whom society had labeled unteachable. One scholar estimated the IQ scores of the children Montessori worked with to be between 50 and 75 (average IQ is 100).

When she began teaching them, she had 60 tearful, frightened children who were so shy she could not get them even to speak. Montessori described a look in their eyes “as though they had never seen anything in their lives.” But Montessori believed that education could transform the lives of these children.

After working with these children for two years, Montessori had them take the public examinations for primary certificates. These exams represented the final milestone of formal education for the average Italian. Merely taking this exam was an impressive feat for these children, but many questioned why Montessori would have “mentally retarded” children take the tests.

But when her six-year-olds performed better than eight-year-olds from the “normal” schools in Rome—all passing both the reading and writing tests—people were shocked. The astonishment was so great that newspapers started writing stories about how the unteachable were surpassing “normal” children.

Questions arose:

How did she do it?

Were these children really mentally deficient?

What does this mean for how we educate?

Montessori cared deeply for the children she taught. But she also cared about the children she did not teach. In taking students from an insane asylum to passing their public examinations, Montessori sent a powerfully symbolic message: If children whom society had cast away could reach the academic proficiency of “normal” children, then perhaps the problem is not the children but the way society educates.

Thereafter, Montessori traveled the world, working in the housing projects of Rome, the slums of London, and with the poor of India to transform the lives of the less privileged through education.

Today, the “Montessori Method” is used throughout schools that bear her name. But in the implementation of particular techniques, we can lose sight of the larger lessons left by the legacy of Maria Montessori’s life. Two of those lessons are 1) a belief that talent is developed rather than innate, and 2) the understanding that learning comes through doing.

A Belief That Talent is Developed Rather Than Innate

The story of Maria Montessori’s journey into education is powerful because she took the children society had cast aside, and showed the world the transformation that can occur through education. She believed in children’s ability to develop talent rather than worrying about who was innately gifted or not.

Research shows that what educators believe about students matters for student learning. Teachers have the power to create a self-fulfilled prophecy with student performance. When we label children as “gifted” or “talented,” we also label all other children as not gifted or talented. Symbolically, this can send a message of higher expectations for learning and performance for some students than for others. Students will work to meet our expectations, no matter how high or low we set them.

A recent study on 15,000 college students examined the effect the mindset of their professors had on student performance. The researchers first measured whether professors had a growth mindset—the belief that talent is developed, or a fixed mindset—the belief that talent is innate. The beliefs of the professors predicted student achievement and motivation above and beyond any other faculty characteristic.

One particularly interesting finding from this study is that the racial achievement gaps in courses with a growth mindset professor were cut in half compared to the gaps in courses taught with a fixed mindset professor. What teachers believe about their students matters for learning.

Understanding That Learning Comes Through Doing

Maria Montessori believed that learning and doing were synonymous. Although Montessori schools have thoroughly developed this idea for young children, all educators can incorporate this philosophy with active learning.

Active learning is anything that students do to learn that goes beyond sitting and listening to a lecture. This does not mean that a teacher sharing information in lecture format to students is a bad thing. It means that the learning experience must also advance beyond just passive listening.

In his book, The Talent Code, Daniel Coyle investigates what makes some educators master teachers. He found that master teachers or coaches have a common obsession with two things: performance and feedback. Great teachers get their students to perform, and they follow that performance with specific, actionable feedback.

This was the key to Maria Montessori’s success. She did not waste her time evaluating potential. Instead, she made learning a “doing experience” in which she could provide consistent feedback on how to improve.

Conclusion

One hundred fifty years after her birth, Maria Montessori’s legacy still has a lot to offer educators today. She traveled the world to provide hope to children by showing them that their ability to learn was far beyond what society had judged. She instilled a growth mindset—the belief that talent and intelligence are characteristics that are developed rather than innately endowed upon a select few.

She also spent the vast majority of her teaching focused on performance and feedback—getting students to learn by doing while providing the needed guidance for improvement. In a time when our educational routines have been upended, perhaps we have an opportunity to reflect on what Montessori’s foundational tenets can mean for learning today.

Useful Resources

- Montessori materials

- Manipulatives

- Montessori Preschool

- Montessori academy

- Montessori daycare

- Montessori method

- Montessori education

- Montessori theory

- Montessori Elementary School

- Montessori High School

- Montessori certification

- Montessori training

- Montessori teacher training

- Montessori method of teaching

- Montessori in real life

- Montessori activities for 2 year olds

- Montessori vs traditional education

- Montessori online school

- Montessori environment

- Montessori online course

- Montessori course

- Montessori and autism

- Montessori and ADHD

- Montessori diploma